Performance of Community Animation Cells in the Management of Emerging Diseases: A Mixed Methods Study from Bukavu, DRC

Siméon Ajuamungu Mushosi

Official University of Bukavu, Health Sciences Domain/Public Health Sector, Kadutu, BP 570, Bukavu, DRC

Lylia Muleko Olela

University of Bordeaux, Public Health School, Bordeaux, France

Florentin Asima Katumbi

Official University of Bukavu, Health Sciences Domain/Public Health Sector, Kadutu, BP 570, Bukavu, DRC

Noémie Kisimba Kapala

University of Lubumbashi, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Public Health, Lubumbashi, DRC

Jean Ahana Bagendabanga

Official University of Bukavu, Health Sciences Domain/Public Health Sector, Kadutu, BP 570, Bukavu, DRC

Criss Koba Mjumbe

University of Lubumbashi, Faculty of Medicine, Department of Public Health, Lubumbashi, DRC

DOI: https://doi.org/10.55320/mjz.52.5.776

Keywords:Community participation, performance, governance, emerging diseases, community animation cell, DRC

ABSTRACT

Background: A community animation unit plays an essential role in the management of emerging diseases by the clear definition of the objectives adapted to this health context and by the effective mobilization of the resources necessary to achieve them. This study aimed to assess the performance of community animation cells in the management of emerging diseases in three health areas in the city of Bukavu.

Methodology: We conducted a study with a mixed quantitative and qualitative method during a period of one month, including 76 members of community animation cells in 38 health areas in the city of Bukavu whose type of sampling was exhaustive; The data was collected with the Kobocollect software and analysed by the STATA-64 and ATLA.TI software for qualitative approaches.

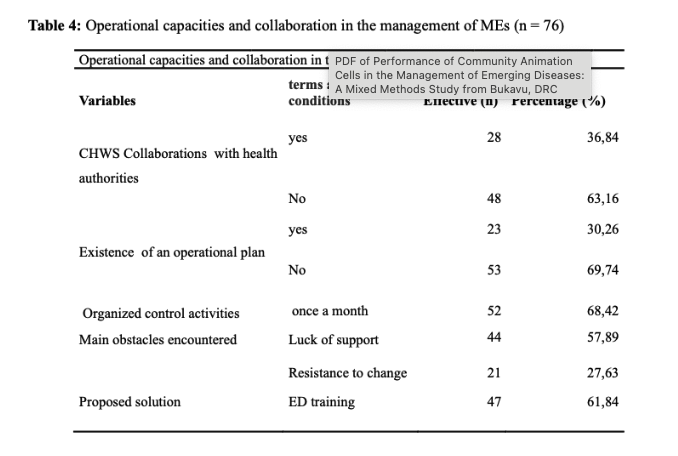

Results: 51% of our sample was married and had already heard of emerging diseases. Among them, 64.47% did not know the meaning of emerging diseases. 57.69% had associated the occurrence of these diseases with styles and life behaviour of the inhabitants; The lack of collaborations between community animation cells and health authorities on the management of emerging diseases have been revealed at 63.16%. 7/10 or 70% of respondents reported the lack of the operational plan developed to combat emerging diseases in their health areas. A greater number had denounced non -support as difficulty, followed by resistance to change, 57.89% and 27.64%; Many have suggested training on emerging diseases and their management as a possible solution (61.84%).

Conclusion: To get to get out of this bottleneck and the low level of performance, one must normally go through a good repetitive collaboration between health authorities and CACs on the management of emerging diseases, which will allow the development of an executive plan to fight these diseases and the training of CACs on the description and management of emerging diseases.

INTRODUCTION

Performance in the public sector is understood as the optimization of the service rendered to citizens; Other theories have also been interested in the question of the evaluation of public sector performance, and more particularly in the health field.[1] Today, the management of emerging diseases (ME) is a major challenge of the 21st century.[2] To deal with it, the World Health Organization has defined primary health care strategies (SSSP) based on essential care, self-responsibility of populations and their ability to self-determinate.[3] This framework requires a multisectoral collaboration, in which community participation is an essential pillar, which cannot be obscured. However, this participation depends, among other things, on the logic of social structures, political organization and a system of representation of society and health.[4] The level of involvement of the populations served by health projects is a necessary condition for the success of the latter.[5] Community participation is indeed the key to the appropriation of any health program for its sustainability. It is one of the principles of primary health care.[6]

Community participation in the different phases of a development project is important.[7] Studies have stressed that if the Community participation is essential for the sustainability of health programs, it often remains confined to planning or implementation, and rarely integrated into the assessment, for lack of appropriate methodological tools. However, an active and enlightened involvement of communities, through community relays, is essential for effective management of diseases. Populations will be willing to modify their behaviour when they are aware of the links that exist between community relays and community health management.[6] African States and International Development and Cooperation Organizations have given African independence, priority to the village approach.[8] In the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), despite ambitious primary health care policies operationalized by health zones and a national 2024-2030 health development plan, the concrete results remain limited.[1]

In Bukavu, community animation cells (CAC) play a central role in awareness and prevention efforts, especially against emerging diseases. However, there is little systematic data on their performance, their specific operational skills, their level of collaboration with other health players, and on the perception of communities of their usefulness.

It is to fill this evidence gap that the present study is intended. It aims to assess the performance of community animation cells in the management of emerging diseases in three health zones in the city of Bukavu, focusing on three essential dimensions:

- The knowledge of CAC members on emerging diseases: their understanding of the issues, prevention mechanisms, and key messages to be transmitted to the population.

- Their collaboration with other stakeholders in the health system (health zones, NGOs, local authorities, etc.): level of integration, coordination, information flow.

- Their operational capacities: available means, tools used, community animation methods, and obstacles encountered in their interventions.

METHODOLOGY

1. Study framework

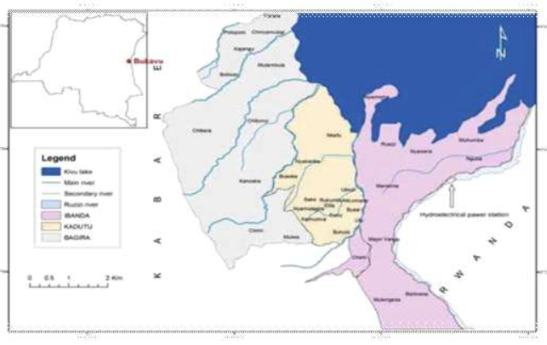

Our study was conducted in the Democratic Republic of Congo, in the three urban health zones of the city of Bukavu, in the province of South Kivu. The health situation in the city of Bukavu is affected by infectious diseases (epidemics of diseases such as malaria, cholera, typhoid fever are frequent, and it is precarious sanitary conditions and limited access to drinking water that exacerbate these health problems). Efforts are made to improve health, but challenges are still persistent.

Type and period of study: this is a mixed study, combining a descriptive quantitative approach and an exploratory qualitative approach. She was taken in three Health zones of Bukavu city: Ibanda, Kadutu, Bagira. The main objective was to assess the performance of community animation cells (CAC) in the management of emerging diseases, through an analysis of individual, collective and organizational dimensions; During the period from January 20 to February 20, 2025.

2. Data collection methods and techniques

Different techniques have helped collect data:

3. Sampling

3.1. Quantitative sampling

The quantitative component was based on an exhaustive sampling of the health development committees (CODESA) active in each health area of the three targeted health zones. An evaluation grid previously tested and articulated on the three dimensions of individual; collective and organizational performance was subject to representatives of community animation cells (Precodesa) and a single member per CAC in each health area that the three health zones of Bukavu city compose.

Thus, all 38 Bukavu health areas were included: the CODESA of each health area as well as a member in each AS was included, a total of 38 precodesa and 38 members.

- Ibanda health zone: 17 health areas

- Kadutu health zone: 13 health areas

- Bagira health area: 8 health areas

In each health area, two people were investigated: Precodesa and an additional member of the codesa, a total of 76 participants (38 precodesa + 38 members) for the quantitative component. These people answered a structured questionnaire, administered using the Kobocollect digital tool.

3.2. Qualitative sampling

For the qualitative component, a reasoned sampling (nonprobability) was used. Participants were selected according to their role, experience and relevance to meet the objectives of the study. It was in particular:

- Of CAC members,

- Of health areas (AS),

- Of community relays,

- And members of households in study areas.

The interviews were carried out until data saturation, until no significant new information emerged from discussions.

4. Inclusion criteria

All participants, both for the quantitative and qualitative survey, had to meet the following criteria:

- Be identified on the official health map of one of the three Bukavu health zones.

- Be active in the area at the time of the survey, with availability confirmed by prior meeting.

- Have at least a year of seniority in the occupied function.

- Have provided informed consent, and agreed to fully respond to the questionnaire or interview

5. Data processing and analysis

Quantitative:

Quantitative data was collected in the field using digital structured questionnaires administered via the Kobocollect application on smartphone or tablet. After verifying their completeness, the data was exported to CSV format then imported and processed with the STATA version 17.0 software.

The analysis followed the following steps:

- Data cleaning: Verification of internal consistency, detection and processing of missing or aberrant values.

- Descriptive analysis: varied united statistics (frequencies, percentages, medium) were produced to describe the socio -demographic characteristics of respondents and the main variables (knowledge of the SEs, transmission and knowledge, etc.) linked to performance (individual, collective and organizational).

- Thematic grouping of indicators: the different variables collected have been grouped in three large dimensions of community performance (individual, collective, organizational) in accordance with the conceptual framework of the study.

- Visualization of results: Tables and graphics (bars, camemberts) were generated to illustrate the distribution of variables and facilitate interpretation.

The analysis did not include inferential statistical tests at this stage, as the main objective was to describe the performance levels and to identify the differences or critical points through an integrated reading with the qualitative data.

Qualitative:

The interviews were recorded, transcribed within the hour according to their realization (Verbatim) under Microsoft Word, then thematically analysed according to the performance axes (individual, collective, organizational) using the Atlas.Ti software. A content analysis was carried out to identify the points of convergence, the deviations, and the structural or contextual factors influencing performance.

The Qualitative approach has aimed to explore in depth the perceptions, experiences and practices of community actors involved in the management of emerging diseases in the three health areas of Bukavu. It made it possible to complete the quantitative results with a contextual understanding of performance dynamics, operational challenges and multisectoral collaboration methods.

a) Data collection tools

The qualitative data was collected using semi-structured maintenance guides developed from the conceptual framework of community health performance. These guides were tested upstream in an area not included in the study to check its clarity and relevance. They covered in particular:

- Collaboration between community and institutional actors in the management of emerging diseases (ME),

- Planning and implementing operational interventions,

- Logistics, human and organizational challenges encountered,

- The mechanisms for assessing and adapting actions in the field,

- Motivation, commitment and community leadership factors.

b) Types of sampling participants and techniques

Reasoned sampling has been used to select key informants. These were people occupying essential roles in local community and health structures, including:

- Health areas (AS),

- Community relays (RC),

- Representatives of beneficiary households,

- Actors from the Central Office of the Health Area (BCZS).

- In -depth individual interviews (IDI): 18 IDIs were conducted (6 per health area) with precodesa, AS managers and community relays.

Members of community animation cells (CAC),

Two types of interviews were carried out:

Focus Group Discussions (FGD): 6 FGD were organized (2 per health zone), each bringing together between 6 and 8 participants from CACs and community relays.

The interviews were conducted in places chosen for their confidentiality, in Swahili or in French according to the preference of the participants, recorded with their consent, then literally transcribed (Verbatim) in the hour according to their realization.

c) Analysis and validation strategies

The analysis was conducted using Atlas software according to a thematic approach. An open coding, followed by an axial coding, made it possible to bring out the categories related to the dimensions of community performance (individual, collective, organizational).

To strengthen the reliability of the analysis:

- Two researchers have independently coded all transcriptions. The differences were discussed until a consensus is obtained.

- A methodological triangulation was applied: the results of the interviews were faced with data from the documentary journal (CAC reports, local action plans, health supervision documents) and to field observations.

- A triangulation of sources was also carried out by comparing the views of the different types of actors (CAC, AS, RC, Households, and Zonal Manager).

d) Reflexivity and attenuation of biases

To limit the interpretation and over -representation biases, a reflexive posture was adopted by the investigators throughout the process. Field logs have been required to note prints, special contexts and methodological adjustments during the investigation.

The effect of social desirability has been attenuated by:

- The training of investigators at active and non -directive listening,

- Strict respect for anonymity and confidentiality of words,

The clear presentation of the study objectives, distinct from any institutional control or evaluation activity.

Certainly, our study was limited to the three health zones of the city of Bukavu. This could lead to a biased selection, as these areas do not represent the set population of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Using the exhaustiveness of all CACs and considering the geographic and demographic diversity of the selected areas, we have taken measures to reduce this bias.

6. Ethical considerations

This study had an authorization from the Ethics Committee of the Official University of Bukavu registered in number 010/2025 and followed the principles required for its realization. All research stages have been carried out in accordance with national and international ethical directives, particularly those stated in the Helsinki declaration. The confidentiality of the data of the participants was strictly respected, and an informed consent was obtained from each member of CAC. Throughout the realization of this work, we scrupulously observed the following scheme: obtain authorization from the Official University of Bukavu via the Public Health Sector to conduct this study, obtaining the informed consent of participants beforehand.

RESULTS

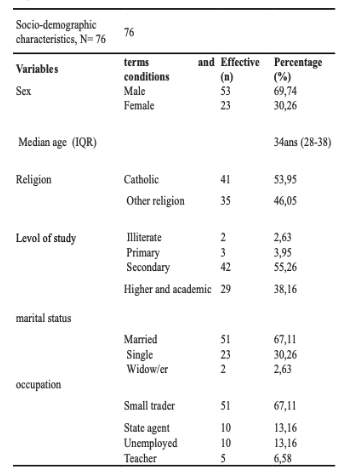

This study included 38 precodesa by CAC with one of its members in three health zones in the Bukavu city, which made a total of 76 members of community animation cells; All agreed to participate in the study. They consisted of 53 men and 23 women with non -sufficient knowledge of emerging diseases in the population.

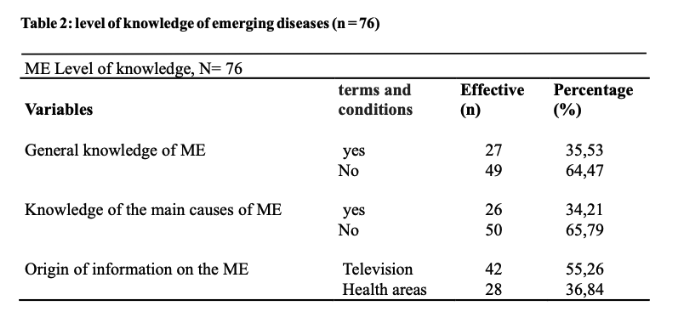

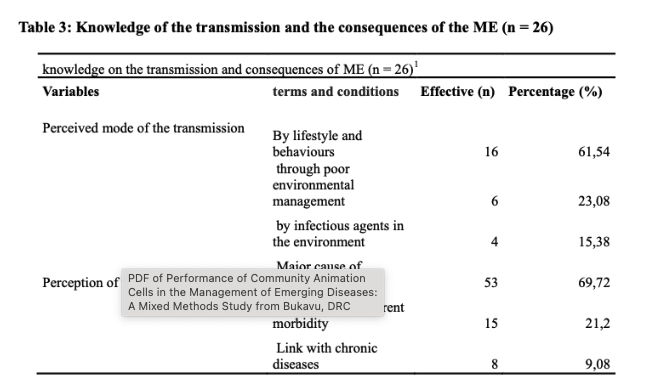

Of the 26 respondents who said they know the main cause of the ME, 61.54% associated its occurrence with a lifestyle and life behaviour.

More than 63 % of respondents indicate an absence of collaboration between the CACs and the health authorities, and 69.74 % declare the inexistence of an operational plan to fight against the ME. More than half of the participants (68.42 %) reported the monthly activity organization. The main obstacles identified were the lack of support (57.89 %) and resistance to change (27.64 %). We noted that 61.84 % of respondents offered training as a solution

Performances of Community Animation Cells (interview)

Production of the services of animators or community relays:The community facilitators have reported their participation at low level in the activities in the community, they expressed irregular outfit of basic meetings, an absence of monitoring of activities, an absence of taking and execution of decisions, and insufficient production of development and organization of quality care instructions, which are mainly linked to available skills.

“Our activities within the community are essentially participation in monitoring and supervisions of the FOSA. Most of those activities are carried out without any expertise. It’s everyone who does what they think he can do well. There is no censorship’’ (AC01).

“We execute the instructions of the health hierarchy the holder nurse ; in all Cases, our activities, our decisions, our meetings, and our AC results do not have curves or monitoring graphs that are displayed.” (AC03)

“I do not have a good memory that we have produced a single instruction for the development or organization of care services, such as on distribution, categorization, reference or the prices for care, at the level of our health area.” (AC06)

Maintenance of culture, motivation and values:AC members have reported the existence of the camps ("supporters" and "opponents" of the nursing in the health centre) creating subgroups following a distrust in the management system. They also reported the existence of a clan culture of IT and ITA, captures of equipment and funds (embezzlement from where communication, integration and weak motivation in AC).

“Camps of person who are ‘’for‘’ or ‘against’ compared to the registered nursing exist in Our team and hamper the coordination and union which should do our work force.” (AC08)

“One of the major problems we have is that the registered nursing takes up equipment and funds for the operation of the health centre and community bodies at the centre. He enjoys it alone, supported by collaborators from his camp and sometimes even by our heads of the hierarchy.” (AC10)

“Communication is not frank in our health area. There is a strong distrust between us and a low transparency between us members of the community animation unit. We pretend to work together; Some do not even know what to be a member of AC.” (AC11)

DISCUSSION

Most CAC members were men (69.74 %), with a 34 -year -old median age, reflecting a relatively young population. A study was carried out in Togo in 2025, where 81% of members of community animation cells were Men, with the median age 41 years.[9] The level of education was generally average; 38.16 % had a higher or academic level, which demonstrates of a certain educational capital, still insufficiently exploited in the fight against emerging diseases (ME). A review of Senegal obtained that most CAC members had a secondary or higher study level, essential for complex awareness tasks in the health sector especially for transmitted diseases.10 However, the high proportion of small traders (67.11 %) and the low representation of professionals in the formal sector (state agents or teachers) reveal a predominance of informal community actors. This can limit access to continuing education and scientific information. Most married people (67.11 %) could nevertheless promote community anchoring and social mobilization, so well supervised. According to the Nordnigeria study, most community animation cells are married, considered more responsible and stable, while according to their professions, the Togolese study shows that the majority made farmers, then small sales in urban areas.[10] [11]

In addition, 64.47 % of CAC members declared that they had no general knowledge of the ME, and 65.79 % did not know their main causes. These figures reveal a serious informational gap in structures however supposed to relay public health messages. This ignorance limits their ability to effectively mobilize the population in the face of emerging health risks in the DRC, a study by Bompangue et al. revealed that less than 40 % of community relays knew how to correctly define emerging diseases (especially zoonoses). According to WHO-Afro in 2023, in more than 10 African countries, less than 50 % of community agents have received formal training on the ME, despite the rise of risks (COVID-19, Ebola, Mpox, etc.).[12] Television (55. 26 %) and health areas (36.84 %) were the main sources of information, which underlines the importance of conventional media and local structures in strengthening health communication. These results call for targeted training campaigns to transform CACs into reliable vectors of dissemination of knowledge on MEs. This reflects vertical media coverage, where information does not always descend to local structures. WHO and UNICEF, however, recommend that it systematically integrate community relays in the communication strategy on risks, Risk Communication and Community Commitment (RCCE), to avoid gaps in the understanding and propagation of false information.[13]

Among the 26 respondents claiming to know the cause of the ME, 61.54 % associated them with individual behaviour, while 15.38 % mentioned infectious agents, which is scientifically more relevant. These perceptions testify to a frequent confusion between the structural and behavioural causes of the ME. It is a partially just perception: individual behaviours (mobility, hygiene, food) influence the emergence of diseases, but zoonotic and environmental factors (deforestation, urbanization, climate change) are scientifically more determining.[14] Regarding the consequences, 69.74 % identified ME as a major cause of mortality, which reveals a partial consciousness of their severity. However, this consciousness is not always accompanied by an understanding of the epidemiological mechanisms, which reduces the capacity of CACs to act upstream (prevention) and calls for training adapted to the concepts of risk, chain of transmission, and community response.

In addition, more than 63 % of respondents indicated an absence of collaboration between the CACs and the health authorities, and 69.74 % declared the non-existence of an operational plan to fight against the ME. These data demonstrate a disconnection between community structures and the formal public health system, harming the coordination of interventions. These results are very worrying, even though public health policies insist on the systematic integration of community structures in response strategies. According to the study by Wurie et al., the low coordination between health structures and communities limited the efficiency of responses to COVID-19 and Ebola in several African countries. The local planning deficit prevents anticipation, community surveillance and rapid management of warning signals.[15]

In addition, the monthly organization of activities, 68.42 % seems insufficient in the context of epidemic risk. These activities are common in the environments where CACs receive neither financing nor formal recognition.16 The main obstacles identified were the lack of support (57.89 %) and resistance to change (27.64 %). In addition, it is encouraging to note that 61.84 % of respondents offered training as a solution, reflecting a desire for improvement, but it is still necessary that this training is structural, practical and regularly updated. Resistance to change is often linked to lack of information, training or local beliefs. The most proposed solution (by 61.84 % of respondents) is the training on the ME, which confirms a strong demand for skills strengthening tools.[16]

The results of this study confirm a significant CAC performance deficit in the management of emerging diseases in Bukavu. Knowledge of ME is very low (64.47 % of members ignore the main causes), which contrasts strongly with the standards observed in other similar contexts. For example, a study conducted in Uganda and South Africa indicates that more than 70 % of community relays have received basic training in epidemiology of emerging diseases.[18] Planning weakness is also worrying. The absence of an operational plan reported by almost 70 % of respondents confirms a deep disorganization of community structures. This joins the observations made in Lubumbashi, where the lack of planning tools and official directives prevented any sustainable coordination of local health actions. The governance dimension is central. Qualitative data reveals a climate of distrust and political divide between CAC members, with the formation of clans around the titular nurses. This clan dynamic mines collective engagement and reduces the effectiveness of interventions.[18] Cases of embezzlement of funds and equipment capturing have also been reported, Compromising the transparency and accountability of CACs. These observations are close to those of Kabeya & Kabey[20] on exclusion dynamics and power games in the community structures of Mbuji-Mayi.

The collaboration between the CACs and the health authorities is insufficient (63.2 % declare the absence of coordination). This limits the multisectoral network, however essential to the response against the ME. The failure of this cooperation was also observed during the response to the COVVI-19 in the DRC, where the health authorities had little integrated community relays into the awareness mechanisms.16 Despite these obstacles, the study also reveals promising tracks: 61.84 % of participants are demanding targeted training. This shows a potential for appropriation and improvement if suitable strategies are implemented. It is necessary to translate these requests into concrete public policies and lasting incentives.

In summary, the CAC performance in Bukavu is compromised by a triple vulnerability: cognitive (low level of knowledge), organizational (absence of planning) and institutional (governance conflicts and poor allocation of resources). To improve this situation, it is essential to strengthen technical capacities and local governance via participatory, transparent and coordinated approaches.

CONCLUSION

This study highlights the vulnerability of Bukavu community animation cells (CAC) in the face of emerging diseases. Despite their central theoretical role in primary health care strategies, CACs suffer from serious shortcomings: a deficit in knowledge, a structural weakness of their organization and governance compromised by internal conflicts and a lack of accountability.

The results reveal a significant disjunction between the potential for community mobilization and the reality of their operation. The Clan conflicts, the appropriation of resources by certain influential members, the absence of a structuring operational plan and the lack of institutional supervision call into question their legitimacy and their effectiveness. To reverse this trend, CACs must be repositioned at the heart of the local health governance system through ambitious reforms. This involves the clarification of their role, the implementation of transparent financing mechanisms, and the valuation of their members by concrete training and incentives.

In addition, the response to emerging diseases requires strong intersectoral coordination. CACs must be able to integrate fully into early alert, epidemiological surveillance and rapid response devices. This requires a strong local and national political will, as well as sustained support from technical and financial partners. CAC could become key players in health resilience in urban environment if the obstacles identified are lifted and if their participation is anchored in inclusive local governance.

Recommendation

1. Capacity

o Develop and disseminate training modules specific to emerging diseases, including crisis communication, identification of weak signals, and community prevention practices.o Organize regular training cycles (every 6 months) with evaluation and certification.

2. Governance and Transparency

o Set up independent CAC monitoring committees, including members of civil society, local authorities and technical partners.o Establish public accountability mechanisms: budget display, community reporting, participatory audits.

3. Integrated community planning

o Co-construct with the CACs an operational plan for monitoring emerging diseases (POCSME).o Integrate operational plans into Devices of health zones with budgetary and technical support.

4. Social digitization and innovation

o Deploy simple digital tools for alert collection, training monitoring, and data ascent (WhatsApp, Kobocollect, SMS).o Develop local communication platforms (community radios, watch -watching groups) to relay key messages.

5. Advocacy and political support

o Awareness of decision -makers of the strategic importance of CACs in public health policies.o Integrate CACs into national strategic plans and in the reform of decentralized health governance.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have not declared any conflict of interest.

ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

AC: Animator Community

BCZS: Central Office of the Health Zone

CAC: Community Animation Cells

COGE: Management Committee

CPN: Prenatal consultation

CS: Health Centre

FGD: Focus Group Discussions

FOSA: Health Training

Idi: In -depth individual interviews

IT: Holder nurse

ME: Emerging Diseases

MAPEPI: Epidemal potentil diseases

Precodesa: Chairman of the Health Development Committee

Reco: Community relay

SNIS: national health information system

SSP: Primary health care

ZS: health zone

REFERENCES

- Pariente H. Detection, investigation and control of emerging diseases in global health [thesis]. Bordeaux: University of Bordeaux; 2022. Supervised by François Dabis.

- Unité de Recherche. Emerging diseases: a challenge for the sustainable development of animal productions. Rev Elev MEd Vet Pays Trop. 2004;17(5):355–63.

- Tingbe-Azalou A. Dynamics of governance of the community relay: logics and play of actors in the Djidja Abomey health zone [dissertation]. 2019.

- Arnault C. Didier Fassin, Political health issues. Senegalese, Ecuadorian and French studies. Man. 2021;(160):215–6.

- Rifkin SB, et al. Community participation in the Village Assaini program. Sheet 9: Evaluate participation. 2021:1–5.

- Bengibabuya D, Karemere H, Hombanyi DB. Community participation in the School and Villages Program sanitized in the Bunyakiri health zone in South Kivu in the Democratic Republic of Congo: issues of appropriation and prospects. Int J Innov Stud. 2022;35(3):492–501.

- Lessault D, Fleuret S. Back and forth between tourism and health: Medical tourism and overall health. Tourism Médical. 2023;7:1–4.

- Artois M, Gilot-Fromont E. Of the risk of emerging illness? 2015.

- Atake EH, Amekudzi LK, Landoh DE. Geographical coverage and dominant socio-demographic profiles of community health workers in Togo. BMC Health Serv Res. 2025;25(1):87.

- Musa E, Osondu C, Auta A, et al. Demographic characteristics and occupational challenges of CHWs in West Africa. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2023;10(4):1231–6.

- Oldo O, Yusuf OB, Bamgboye EA. "We just have to help": perceptions and roles of community health workers in hypertension and diabetes care in Nigeria. Hum Resour Health. 2023;21(1):27.

- World Health Organization Regional Office for Africa. Strengthening community protection and resilience: regional strategy for community commitment 2023–2030 in the WHO African Region [Internet]. Brazzaville: WHO AFRO; 2023 [cited 2025 Jul 18]. Available from: https://www.afro.who.int/

- UNICEF, WHO. RCCE Readiness and Response: Lessons from COVID-19 and Ebola. Geneva: WHO; 2023.

- Jones KE, Patel NG, Levy MA, et al. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases: the role of land use and human–animal interaction. Lancet Planet Health. 2023;7(2):e142–50.

- Wurie HR, et al. Community commitment failures during disease outbreaks in Africa: a lesson from Ebola and COVID-19. BMJ Glob Health. 2023;8:e012345.

- Okee J, Takahashi E, Otshudiema JO, Malembi E, Ndaliko C, Mu M, et al. Strengthening community-based surveillance: lessons learned from the Ebola epidemic (2018–2020) in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Pan Afr MEd J. 2023;41:1–X.

- Sanogo B, Diarra B, Sangho H, Iknane AA. Level of satisfaction of hospital patients in the Koutiala health district, Mali. Mali Public Health. 2019 Jun. Also in: National Plan for Sanitary Development Recadre for the period 2019–2022: towards universal health coverage. Kinshasa: PNDS; 2019.

- Wongcharoen N, Srirattayawong T, Panta P, Ngokulna K, Teachasub J, Somboon T, et al. Effects of experiential learning program of community health workers on health literacy and preventive behaviours of emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases of the respiratory system. 2024.

- Le Her C. Description and commitment in the activity of the pedagogical animation cells in Senegal: between institutional prescriptions and teachers’ perceptions in Dakar and Casamance [thesis]. 2024. HAL Id: tel-04836952.

- Kabeya C, Kabey. Determinants of the use of healing services and therapeutic tracks in Mbuji-Mayi, DRC. Med J. Zambia 2025;52(1):5–15. doi: 10.55320/MJZ.52.1.612.

Medical Journal of Zambia, Vol 52, 5

The Medical Journal of Zambia, ISSN 0047-651X, is published by the Zambia Medical Association.

© This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.