Behind the Control Panel: A qualitative exploration of the Ethical Dilemmas Faced by Radiographers

Theresa Upare, Bornface Chinene

1Harare Institute of Technology, Department of Radiography, Belvedere, Zimbabwe

DOI: https://doi.org/10.55320/mjz.51.4.591

Keywords:Ethical Dilemmas, Radiographers, Patient Care, Moral Distress, Coping Strategies

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Understanding ethical dilemmas is crucial as they enhance patient care and safety practices. The Zimbabwean healthcare environment, characterized by a shortage of equipment, poor remuneration, overcrowding of patients, and a massive exodus of workers, has been shown to increase the prevalence of ethical dilemmas faced by radiographers. This study aimed to explore the ethical dilemmas encountered by radiographers and the coping strategies they employ at central hospitals in the Harare Metropolitan Province, Zimbabwe.

Methods: The study employed a qualitative exploratory design employing in-depth interviews. A total of 10 participants were recruited to explore the ethical dilemmas experienced by radiographers at 3 public hospitals in Harare. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Data management was done in Nvivo 13 and six-step thematic analysis according to Braun and Clarke was used to analyse the data.

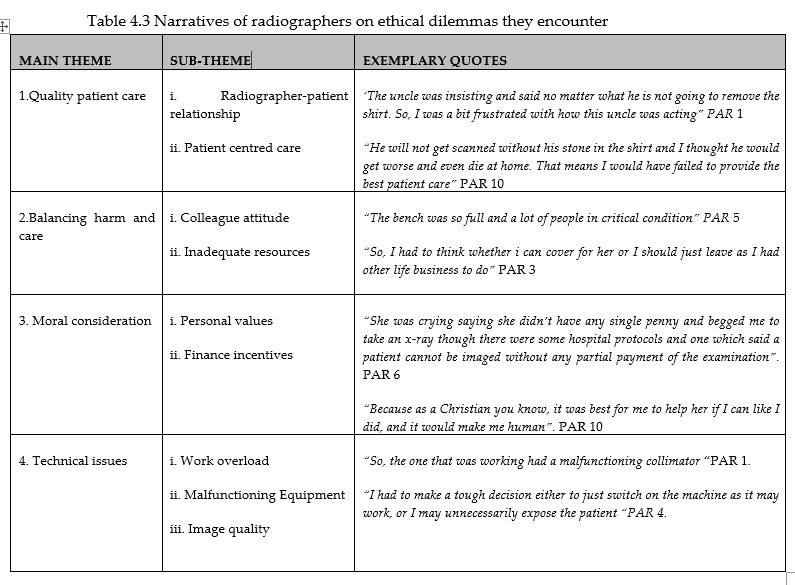

Results: Four themes explaining ethical dilemmas faced by radiographers were created, including i. quality patient care, ii. balancing harm and care, iii. moral consideration, and iv. technical issues. Four themes representing the coping strategies employed by radiographers were also created, including i. expressing oneself, ii. human dignity, iii. maintaining professionalism, and iv. reference points.

Conclusion: The study suggests that radiographers face ethical dilemmas, leading to moral distress and compromising their professional values. It underscores the importance of regularly assessing ethics during decision-making to reduce these issues and maintain professional integrity.

Implications for practice: The study emphasizes the importance of integrating ethical training and support systems for radiographers to enhance patient care, protect professional integrity, and reduce moral distress.

INTRODUCTION

Assessing ethical dilemmas is essential to understanding how well ethical principles are applied in radiography practice [1] . An ethical dilemma is defined as a situation where a choice has to be made between competing values, and no matter what choice is made, it will have consequences [2] . In other words, a dilemma may be if the radiographer is forced to choose between options that are considered equally desirable or undesirable but may also occur when forced to compromise or act against their professional values. Examples of ethical dilemmas that may be faced by radiographers that can significantly impact their practice and decision-making include; informed consent issues, confidentiality, risk-benefit evaluation of radiation exposure, prioritizing imaging requests, professional boundaries, equipment shortages, communication of findings and dealing with incomplete request forms [3] .

Ethical dilemmas are important in radiography because they have significant implications for radiation protection, patient care, professional standards, interprofessional collaboration, and the overall effectiveness of healthcare delivery [4,5] . Addressing these dilemmas is crucial for ensuring ethical practices that prioritize the well-being of patients and the integrity of the radiography profession [6] .

The Zimbabwean healthcare environment is characterized by a shortage of equipment, poor remuneration, overcrowding of patients, and a massive exodus of workers [7-9] . These factors have been shown to increase the prevalence of ethical dilemmas faced by radiographers, particularly concerning resource allocation, compromised patient care due to operational constraints, and handling inaccurate referrals [10,11] (10,11). Hence, understanding the types and nature of ethical dilemmas the radiographers face in Zimbabwe can help them develop skills that improve patient care and safety which will raise the standard of radiography practices [4] . Despite the importance of these dilemmas, there is a rarity of research documenting the ethical challenges encountered by radiographers, resulting in their underrepresentation in professional literature [12] . Numerous studies have been done in other healthcare professions like nursing, medicine and rehabilitation[2 ,4,13-15] . These studies indicate that there is a lack of an appropriate, objective, and unified approach to effectively guide healthcare workers in addressing these challenges.

Building on this foundation, the present study sought to explore the ethical dilemmas experienced by radiographers and the coping strategies they employ at central hospitals in Harare Metropolitan Province (HMP), Zimbabwe. By investigating these dilemmas, this study expects to improve radiographers' understanding of ethical dilemmas, enhancing service delivery and patient care. It also seeks to encourage ethical discussions within professional bodies and the developing of coping strategies to mitigate negative impacts on professionalism, thereby enhancing patient experiences and safety.

METHODS

Study design

This study utilized a qualitative exploratory design, employing in-depth interviews for data collection. This design was suited for this study as it provided rich insights into radiographers' perspectives on their experiences with ethical dilemmas in their respective departments [16] . The in-depth interviews facilitated rapport between the researcher and participants, encouraging them to share honest and open responses. Additionally, this method allowed the researcher to gain a deeper understanding of the individual experiences that influence each radiographer's situation.[17]

Research setting

The study was carried out at three central hospitals in HMP. Central hospitals provide specialized medical services to mostly the urban population. They offer comprehensive services, including emergency care, surgical procedures, maternity care, radiology, radiotherapy, nuclear medicine, and other specialized clinics. However, they often operate at full capacity, leading to overcrowding and long wait times.[7] The healthcare workforce is diverse, but challenges include limited financial resources, outdated equipment, and inadequate infrastructure.[18,19] The central hospitals also play a crucial role in public health, serving as referral centres for smaller health care centres and contributing to health education and community health initiatives .

Population

The target population for this research was all radiographers working in public hospitals in HMP who are approximately 50 in total, according to the Allied Health Practitioners Council (AHPCZ) register. For this study, the researchers focused with the ethical dilemmas the radiographers face in their clinical practice of general x-rays, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or ultrasound imaging.

Sampling size and sampling procedure

Purposive sampling was employed to select participants working in general radiography, CT, MRI and ultrasound imaging. The researcher focused on radiographers with two or more years of experience, as they are likely to have encountered a greater number of ethical dilemmas in their clinical practice and could offer more informed insights. According to the AHPC registry, there were approximately 50 registered diagnostic radiographers based in public hospitals in HMP, of which 16 have less than two years of experience. Qualitative studies typically have smaller sample sizes compared to quantitative studies, with numbers ranging from 5 to 20 participants. To determine the final sample size, researchers apply the principle of saturation, which indicates that data collection can continue until no new information or themes emerge from the participants. This principle guided the decision on how many participants were ultimately recruited for this study[21] . Literature indicates that qualitative research can achieve data saturation with fewer participants than initially planned.[21] Therefore, it was determined that further interviews with the remaining participants would not be necessary, as their contributions would likely yield similar information.

The inclusion criteria for this study were as follows:

- Radiographers currently working in public hospitals who agreed to participate.

- Radiographers with a minimum of two years of experience.

- Radiographers registered with the AHPCZ.

Conversely, the exclusion criteria included:

- Radiographers who were unwilling to participate in the study.

- Other healthcare professionals working in the radiography department.

- Radiographers not registered with the AHPCZ.

This approach ensured that the study focused on qualified and experienced radiographers, providing valuable insights into their experiences with ethical dilemmas.

Data collection instrument

This research utilized an interview guide for data collection. The guide included demographic information about the participants, which was essential for the study. The interview was divided into three sections: Section A contained opening remarks, where the researcher introduced herself, explained the purpose of the interview, and clarified how the information gathered would be used. Demographic characteristics were also captured by this section. Section B consisted of the questions posed during the interview to gather the necessary information. The questions were developed through consultations with radiographers in academia to identify the best methods for extracting the required information.[17] A literature review was conducted to create relevant questions, drawing from studies by Lewis et al. [5] , Ahenkan et al. [10] , and Haahr et al. [2] . Additional resources were obtained from the Institute library which provided past research projects and interview guides to help formulate suitable questions for this study. The last section (C) constituted closing remarks as the participation of the participant was appreciated.

Data collection procedure

In-depth interviews lasting between 25 to 50 minutes were conducted to gather information from radiographers. Potential participants, specifically those with two or more years of experience working in public hospitals in Harare, were contacted via telephone or email and invited to participate in the study at a time that was convenient for them. The interviews took place at the research sites, also scheduled according to the interviewees' availability. To ensure high-quality recordings, the interviews were audio-recorded using an Android phone equipped with a voice digital recorder application. This application enhanced voice clarity and made playback easier for transcription purposes. The first author (T.U) transcribed the voice-recorded interviews verbatim.

Data analysis

The interview data were analysed using thematic analysis, following the six-step framework established by Braun and Clarke [22] . The analysis process consisted of several key steps:

- Familiarization with the Data: The first researcher began by immersing herself in the data during collection, identifying patterns of meaning and issues of interest. This involved transcribing the interviews and noting initial ideas and potential coding schemes.

- Generating Initial Codes: The next step involved creating initial codes by connecting the identified patterns with relevant literature related to the study. This allowed for a deeper understanding of the findings. Both authors, (T.U. and B.C.), created the codes independently, and any differences were resolved through consensus

- Searching for Themes: In this step, the researchers gathered all relevant data associated with each potential theme, organizing the information to identify broader patterns.

- Reviewing Themes: The themes that were created were then reviewed to ensure they coherently related to the coded extracts from the initial steps. This review helped form a thematic map of the analysis.

- Defining and Naming Themes: The researchers defined each theme clearly and assigned names to specify their focus, ensuring clarity in what each theme represented.

- Producing the Report: Finally, the findings were compiled into a report presented in a table format. This structured presentation allowed for a comprehensive analysis of the selected themes, linking the interpretations back to the research questions and relevant literature. This systematic approach enabled the research to uncover meaningful insights from the interview data.

Trustworthiness and integrity of study

Lincoln and Guba [23] criteria including credibility, dependability, confirmability, and transferability was used increase trustworthiness of this study. Credibility was achieved by allowing radiographers to verify the accuracy and relevance of the results to their own experiences (member checks) [24] . Additionally, triangulation was employed by including participants with varied backgrounds, such as different radiography centres and levels of experience [17] . Transferability was established by demonstrating how the study's findings can apply to various contexts, situations, populations, and demographics. The rigor with which the research was conducted, analysed, and presented contributed to the dependability of the findings. Each phase of the study was described in detail, allowing for the possibility of replication to yield similar results. Furthermore, the researchers ensured that the participants’ responses were rich, detailed, and in-depth by asking broad and open-ended questions, enhancing the study's dependability[25] . Confirmability was achieved by documenting the methodology used in conducting the study, as well as how the data was analysed, thereby enhancing the study's validity[25] .

Ethical considerations

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Medical Research Council of Zimbabwe (MRCZ number B/2431). An approval letter was also secured from the participating centres for this study. Before participating, all individuals filled out an informed consent form. To uphold the ethical standards of privacy and confidentiality, all collected information was anonymized. Furthermore, the data gathered was used solely for the purposes of this research.

RESULTS

A total of 10 practicing radiographers took part in the interviews. Table 4.2 gives a summary of the participant demographic characteristics.

Ethical Dilemmas faced by radiographers at Public Hospitals in HMP

This section explores the ethical dilemmas radiographers face in public hospitals in the HMP. The findings are organized into four main themes: Quality Patient Care, Balancing Harm and Care, Moral Consideration, and Technical Issues.

THEME 1: QUALITY PATIENT CARE

i. Radiographer-Patient Relationship

A number of participants reported ethical dilemmas regarding how to interact with patients while ensuring they received optimal care. Radiographers often grappled with their own frustrations when patients struggled to understand procedures.

"I had to explain to him one thing more than five times, and I was frustrated as he was already tempering with my temper." (PAR 3)

ii. Patient-Centred Care

Participants also indicated that their decisions were influenced by emotions such as irritation and frustration, particularly in situations where patients exhibited challenging behaviour. One radiographer recounted an incident where a patient's relative was disruptive, saying,

"The uncle was insisting that no matter what, he was not going to allow the procedure. I was frustrated with how this uncle was acting, especially with a whole bench full of patients needing my assistance. I needed to make a quick and better decision." (PAR 1)

THEME 2: BALANCING HARM AND CARE

i. Colleague Attitude

Radiographers described facing ethical dilemmas when their colleagues' attitudes affected patient care. Some participants mentioned that the efficiency of the workflow in the radiology department was disrupted by colleagues, leading to delayed care for patients.

"This was affecting the patient with delayed care, and I felt we were doing our best. I had to decide whether to confront my colleagues about their actions." (PAR 2)

ii. Inadequate Resources

Inadequate resources in public hospitals also presented challenges when making ethical decisions. Radiographers reported that limited supplies often hindered their ability to provide care effectively.

"The resources we have in government hospitals are few, and we do not always receive what we request from procurement, which affects the decisions I must make." (PAR 8)

“Another noted, "PPE may not be available, and my health matters too, so I have to assess the situation carefully." (PAR 9)

THEME 3: MORAL CONSIDERATION

i. Personal Values

Participants expressed that their personal values significantly influenced their ethical decision-making. Many radiographers shared experiences where they faced dilemmas aligning with their beliefs.

"We have to respect each other's religions because people believe in different things. A colleague said it was wrong to accommodate the patient's needs, but I felt compelled to act based on my values." (PAR 2)

ii. Financial Incentives

Ethical dilemmas also arose when patient finances conflicted with radiographers' professional ethics. Participants described situations in which patients attempted to bribe them or coax them into unethical practices.

Another noted the pressure from influential patients, saying, "I’ve encountered patients wanting to change their scan dates, and some of these individuals hold significant power in the government." (PAR 9)

Additionally, participants reported feeling conflicted when faced with patients who required urgent care but lacked the financial means to pay.

"Patients come requesting an x-ray but may not have money. According to hospital policy, I should send them back, but if the patient is critical, I often face a moral dilemma about whether to proceed with the imaging to save their life." (PAR 6)

THEME 4: TECHNICAL ISSUES

i. Work Overload

Many radiographers reported experiencing ethical dilemmas related to work overload, particularly during equipment failures or emergencies.

"When machines break down, we cannot provide optimal care for inpatients. I often have to decide whether to work with malfunctioning equipment." (PAR 1)

Another added,"We would try to perform a CT scan, but the machine would malfunction, which affects the power system and may erase data. I need to decide whether to continue or abandon the exam." (PAR 5)

ii. Malfunctioning Equipment

Most participants indicated that the recurring malfunction of machines hindered their ethical responsibilities. When equipment failed, radiographers faced tough decisions on whether to attempt temporary repairs or risk patient safety by using malfunctioning devices.

"The queue of patients is long, and I believe it’s unfair to expose a paediatric patient to radiation with an uncollimated beam. I face a dilemma: do I adjust the settings and risk a lower-quality image, or do I wait for repairs?" (PAR 10)

Overall, the ethical dilemmas faced by radiographers in public hospitals underscore the complex interplay between patient care, resource availability, and personal values, highlighting the critical need for systemic improvements in the healthcare context.

iii. Image Quality

Concerns regarding image quality due to equipment malfunctions were also prevalent. Radiographers expressed fear of exposing patients to unnecessary radiation or producing subpar diagnostic images.

"With the collimator wide open, there is much scatter radiation delivered to the patient, and the image may not be diagnostically useful. It becomes a tough decision whether to continue." (PAR 10)

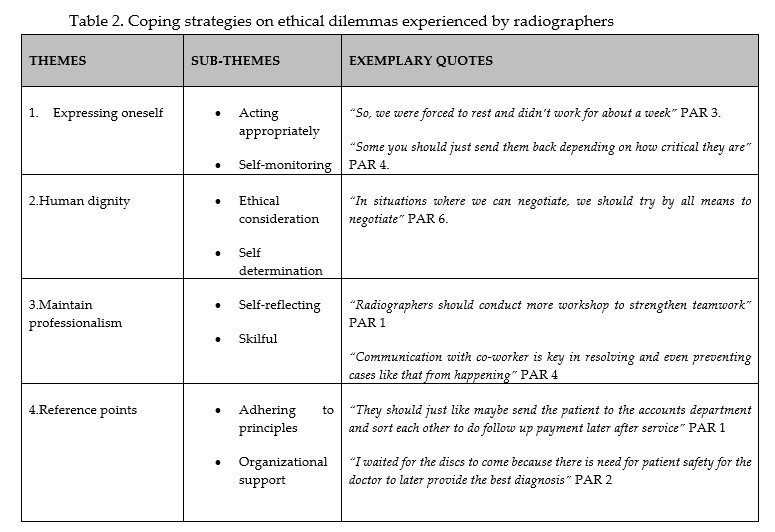

Coping strategies for Ethical Dilemmas

Radiographers at public hospitals in HMP navigate a range of ethical dilemmas, utilizing various coping strategies that can have both positive and negative effects on their professional well-being. Through in-depth interviews, participants shared strategies that others in similar situations might find helpful. The coping strategies are categorized into four main themes.

THEME 1: EXPRESSING ONESELF

i. Acting Appropriately

Some respondents emphasized the importance of ethical decision-making when providing care. They sometimes offered free services to patients in need, although this created financial concerns for the hospital. One participant articulated this dilemma by saying,

"Although I know the client will only pay for one procedure, I can't just scan anyone who comes without money, as it leads to financial losses for the hospital." (PAR 6)

Another radiographer shared a more personal account:

"I treated a patient who couldn't pay, and although it was a secret, I felt it was the right thing to do." (PAR 1)

However, others indicated that they would still deny care if patients couldn't pay, as one participant noted,

"If they do not have money, I send them back, even if I want to help." (PAR 6)

ii. Self-Monitoring

Many participants reported using rest breaks as a coping mechanism, allowing them to manage their stress and make thoughtful decisions. This approach helped them maintain care standards and adhere to radiation safety protocols. One radiographer explained,

"When the collimator light was malfunctioning, we opted to take a break rather than risk exposing patients to excessive radiation." (PAR 1)

THEME 2: HUMAN DIGNITY

i. Ethical Consideration

In navigating ethical dilemmas, some respondents focused on balancing patient needs with institutional policies. They aimed to uphold ethical principles by negotiating outcomes that considered all parties involved.

"I don’t take any action beyond my role; I advise the patient to consult their doctor and let them handle it." (PAR 6)

ii. Self-Determination

Radiographers demonstrated a strong commitment to saving lives, often prioritizing critically ill patients.

"It’s better to prioritize incoming patients in serious condition, or I’ll call someone on shift to address urgent cases." (PAR 3)

THEME 3: MAINTAINING PROFESSIONALISM

i. Self-Reflection

Communication among colleagues was cited as a critical coping strategy, allowing for self-reflection and problem-solving.

"We must communicate openly. Maybe a colleague is dealing with pressing concerns, and we reach out to each other." (PAR 4)

ii. Skillfulness

To cope with ethical dilemmas, many radiographers highlighted the significance of professionalism and skill. They reported that maintaining high standards reduces negative outcomes, especially when colleagues cover for one another during absences.

"Even if I leave my post unattended, we must always support our patients by providing care." (PAR 7)

THEME 4: REFERENCE POINTS

i. Adhering to Principles

When faced with ethical dilemmas, some radiographers stressed the importance of making principled decisions, regardless of potential outcomes. One participant suggested,

"If there are issues, patients should be referred to the accounts department for resolution, where they can address financial matters later." (PAR 1)

ii. Organizational Support

Most radiographers identified the importance of institutional support in coping with ethical dilemmas. They emphasized starting with organizational resources as a strategy for effective decision-making.

‘Having well-serviced machines and available resources simplifies our work." (PAR 4)

Another emphasized the importance of directing patients appropriately:“In some cases, we should refer patients to other institutions that can assist and advise those who are in a hurry to return when the equipment is functional." (PAR 9)

In conclusion, the coping strategies employed by radiographers in public hospitals highlight the complexities of balancing ethical responsibilities, personal values, and professional standards in challenging healthcare environments.

DISCUSSION

Ethical dilemmas are complex situations that radiographers frequently encounter, affecting their ability to make sound moral decisions while maintaining high standards of patient care.[3] This study aimed to explore the ethical dilemmas faced by radiographers and the coping strategies they employ at central hospitals in the HMP, Zimbabwe. The findings reveal the intricate interplay between patient care, resource allocation, personal values, and professional ethics that radiographers navigate in public hospitals. Daily, they confront various ethical challenges across different work environments.

This research is significant as it represents the first qualitative study exploring the insights of radiographers in Zimbabwe regarding their ethical dilemmas. By utilizing in-depth interviews, the study gathered extensive understandings into the experiences of radiographers working in public hospitals. In contrast to previous studies involving other healthcare professions [2,4 ,13-15] , this research emphasizes the uniqueness of radiographers in the Zimbabwean setting.

The current study highlights the critical nature of the radiographer-patient relationship as a factor in ethical dilemmas. The findings reveal that effective communication is essential for optimal care, and any misunderstanding can lead to frustration and emotional strain for radiographers, undermining their patient-centred approach. The complexity of medical jargon in radiographic procedures can lead to misunderstandings and confusion among patients, especially in vulnerable or urgent medical situations. In these ethically complex scenarios, effective communication becomes essential for managing emotions and enhancing the understanding of medical information. It also helps to better identify patients' needs, perceptions, expectations, and values [26-28] . Research shows that good communication can significantly improve patient and family satisfaction, ease the adjustment to illness, increase adherence to medical treatments, and ultimately lead to better clinical outcomes [29,30] (29,30). Radiographers can enhance patient communication by utilizing Layman's Terms, offering visual aids, encouraging questions, repeating key information, and providing written consent forms[3] . These strategies ensure patients are fully informed about procedures, leading to better outcomes and satisfaction.

Additionally, technical issues such as equipment malfunctions and work overload exacerbate these challenges, as they can compromise patient safety and compel radiographers to make difficult decisions under suboptimal conditions. The healthcare environment in Zimbabwe is characterised by a lack of adequate equipment, low salaries, crowded facilities, and a significant exodus of healthcare workers [7-9] . These issues contribute to an increase in ethical dilemmas for radiographers, particularly regarding resource allocation, compromised patient care due to operational constraints, and dealing with inaccurate referrals [10 ,11] . Ultimately, these findings highlight the systemic challenges within public healthcare that make it difficult for radiographers to uphold ethical standards and provide high-quality patient care.

In general, the findings of this work show that radiographers regularly face ethically challenging situations in their daily practice. Although they can often recognize the appropriate actions to take, they sometimes struggle to implement these solutions. While numerous studies have documented the ethical challenges faced by healthcare workers [2,4 ,13-15] , a gap remains in understanding how they cope with these situations.

One major coping strategy identified by radiographers in this study is the theme of self-expression, which helps radiographers mitigate the mental toll of facing ethical dilemmas. By taking active steps aligned with their values and maintaining professionalism, they can better handle these challenges [3] . Additionally, the theme of human dignity emerged as a prominent coping strategy among radiographers confronted with ethical dilemmas. They often prioritize saving lives, even if it means deviating from strict laid-down hospital procedures. Radiographers frequently negotiate with patients to ensure they will not regret their decisions later. Bishop and Scudder [31] , argue that ethical dilemmas place healthcare workers in a unique position essential for decision-making, highlighting the importance of individual values in coping with these ethical challenges. Lastly, participants highlighted the importance of organizational support in addressing ethical dilemmas. Resources and procedural guidelines were seen as crucial for effective decision-making. Referring patients to appropriate channels for addressing financial concerns can alleviate pressure on radiographers and allow them to focus on delivering quality care. This is significant, considering the systemic issues that play a crucial role in exacerbating the ethical dilemmas faced by radiographers in Zimbabwe[7-9] .

To address ethical dilemmas faced by Zimbabwean radiographers due to systemic factors, long-term strategies include implementing ethical training programs, promoting open communication, and establishing tailor-made guidelines. At an organizational level, collaborating with other healthcare professionals and advocating for policy reforms to prioritize resources, fair work conditions, and ongoing education will also help create a sustainable and ethically sound practice environment.

Limitations of the study

The focus on radiographers in public hospitals in HMP may limit the generalizability of the findings to other healthcare settings and regions, as different cultural and institutional contexts may influence the ethical dilemmas faced by radiographers. Furthermore, the reliance on in-depth interviews, while providing rich qualitative data, may introduce biases based on participants' self-reports and perceptions, which could be influenced by social desirability or recall bias. Future research should explore the long-term effects of ethical dilemmas on the well-being and career trajectories of radiographers, as this could provide valuable insights into the implications of these challenges.

CONCLUSION

The study reveals that radiographers' ethical conduct is significantly influenced by their work environment highlighting entrenched systemic issues. It highlights the challenges faced by them in public hospitals, which are often related to ethical concerns. Addressing these issues is crucial to uphold radiographers' fundamental ideals and prevent moral distress. Understanding these ethical dilemmas is essential for fostering ethical conduct within the profession, as they can lead to conflicts, uncertainties, and challenges. By addressing these dilemmas, we can improve ethical standards in radiography and enhance patient outcomes, which is the primary goal of healthcare departments.

Declaration.

No conflict of interest to declare. ChatGPT has been used to improve only the readability of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Kooli C. COVID-19: Public health issues and ethical dilemmas. Ann Oncol. 2020;(January):19–21.

- Haahr A, Norlyk A, Martinsen B, Dreyer P. Nurses experiences of ethical dilemmas: A review. Nurs Ethics. 2020;27(1):258–72.

- American Professional Guide. Ethical Dilemmas in Radiologic Technology [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2024 Oct 30]. p. 1–10. Available from: https://americanprofessionguide.com/ethical-dilemmas-in-radiologic-technology/#google_vignette

- Camargo A, Yousem K, Westling T, Carone M, Yousem DM. Ethical dilemmas in radiology: Survey of opinions and experiences. Am J Roentgenol. 2019;213(6):1274–83.

- Lewis S, Heard R, Robinson J, White K, Poulos A. The ethical commitment of Australian radiographers: Does medical dominance create an influence? Radiography. 2008;14(2):90–7

- Lewis S. Reflection and identification of ethical issues in Australian radiography: a preliminary study. Radiogr. 2002;15(1):37–48.

- Chinene B, Bwanga O. Exploring the perceptions of radiographers pertaining to the provision of quality radiological services in Zimbabwe. J Med Imaging Radiat Sci [Internet]. 2023;54(3):634–43. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmir.2023.07.013

- Maboreke T, Banhwa J, Pitcher R. An audit of licenced Zimbabwean radiology equipment as a measure of health access and equiry. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;36(60):1–11.

- Hinrichs-Krapels S, Tombo L, Boulding H, Majonga ED, Cummins C, Manaseki-Holland S. Barriers and facilitators for the provision of radiology services in Zimbabwe: A qualitative study based on staff experiences and observations. PLOS Glob Public Heal [Internet]. 2023;3(4):e0001796. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0001796

- Ahenkan A. Ajol-File-Journals_545_Articles_176337_Submission_Proof_176337-6421-450873-1-10-20180817.Pdf.

- Lategan L, Van Zyl G, Kruger W. What social determinants will cause ethical challenges in geriatric care? Comments from South Africa. J Public Health Africa. 2023;14(5):76–80.

- Pettigrew A. Ethical issues in medical imaging: Implications for the curricula. Radiography. 2000;6(4):293–8.

- Bollig G, Schmidt G, Rosland JH, Heller A. Ethical challenges in nursing homes - staff’s opinions and experiences with systematic ethics meetings with participation of residents’ relatives. Scand J Caring Sci. 2015;29(4):810–23.

- Hopia H, Lottes I, Kanne M. Ethical concerns and dilemmas of Finnish and Dutch health professionals. Nurs Ethics. 2016;23(6):659–73.

- Barnitt R. Ethical dilemmas in occupational therapy and physical therapy: A survey of practitioners in the UK National Health Service. J Med Ethics. 1998;24(3):193–9.

- Magaldi D, Berler M. Semi-structured Interviews. In: Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences [Internet]. 2020. p. 4825–30. Available from: www.iosrjournals.org

- Polit FD, Beck TC. Nursing Research. Principles and Methods. 7th ed. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2014. 746 p.

- Breaking News: Doctors and nurses stage demonstration in Harare [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jun 23]. Available from: https://savannanews.com/doctors-nurses-strike-go-on-strike-stage-demonstration-in-parirenyatwa-harare/

- Muronzi C. Zimbabwe healthcare workers strike over wages , inflation crisis [Internet]. Al Jazeera. 2022. Available from: https://www.aljazeera.com/economy/2022/6/20/zimbabwe-healthcare-workers-strike-over-wage-crisis

- Care ZM of H and C. Zimbabwe National Health Staretgy 2021-2025. Harare: Government Printers; 2021.

- Fusch PI, Ness LR. Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. Qual Rep. 2015;20(9):1408–16.

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol [Internet]. 2006 [cited 2021 Apr 8];3(2):77–101. Available from: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/uqrp20

- Lincoln YS, Guba EG. Naturalistic Inquiry. Sage Publications. Newbury Park, CA; 1985. p. 415.

- Arora AB. Member Checks. In: The International Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods [Internet]. Wiley; 2017 [cited 2020 Aug 7]. p. 1–3. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0149

- Nowell LS, Norris JM, White DE, Moules NJ. Thematic Analysis : Striving to Meet the Trustworthiness Criteria. Int J Qual Methods. 2017;16:1–13.

- Ha JF, Hons M, Anat DS, Longnecker N. Doctor-Patient Communication : A Review Doctor-Patient Communication : A Review. 2014;(April 2010).

- Bouleuc C, Dolbeault S, Bre A. Doctor-patient communication and satisfaction with care in oncology. Curr Opin Oncol. 2005;17:351–4.

- Arora NK. Interacting with cancer patients: The significance of physicians’ communication behavior. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(5):791–806.

- Meyer EC, Sellers DE, Browning DM, McGuffie K, Solomon MZ, Truog RD. Difficult conversations: Improving communication skills and relational abilities in health care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2009;10(3):352–9.

- Wright Nunes JA, Wallston KA, Eden SK, Shintani AK, Ikizler TA, Cavanaugh KL. Associations among perceived and objective disease knowledge and satisfaction with physician communication in patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int [Internet]. 2011;80(12):1344–51. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/ki.2011.240

- Bishop AH, Scudder JR. A Phenomenological Interpretation of Holistic Nursing. J Holist Nurs. 1997;15(2):103–11.

Medical Journal of Zambia, Vol 51, 4

The Medical Journal of Zambia, ISSN 0047-651X, is published by the Zambia Medical Association.

© This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.